Intimate partner violence linked to delays in contraceptive care

September 24, 2025

Access to birth control is crucial for young people’s reproductive autonomy. Many young people rely on a range of birth control methods to control the timing, spacing, and number of pregnancies.

Clinicians don’t feel confident helping adolescents get abortion care

August 13, 2025

A new study published in Contraception found that less than half of clinicians felt confident helping adolescents navigate the logistics of getting abortion care.

Young women have a range of feelings about pregnancy

July 23, 2025

Defining pregnancy as a binary between intended and unintended doesn’t capture this range of feelings. When people are given more options, they express ambivalence. A new paper led by Sarah Nathan, PhD, explores the pregnancy preferences of young women age 15-24, using the Desire to Avoid Pregnancy...

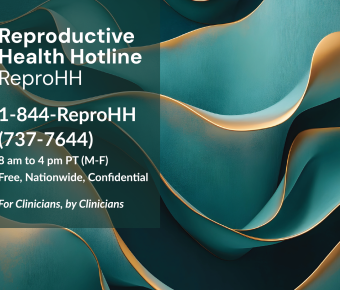

Elevate your reproductive health knowledge with the Reproductive Health Hotline

July 02, 2025

The Reproducitve Health Hotline (ReproHH) is staffed by dedicated UCSF physicians, with specialized expertise in sexual and reproductive health, who are ready to support you in providing the highest quality care to your clients.

Changing futures through soccer and sexual health

June 16, 2025

Integrating sports and sexual health could be an innovative and effective approach for promoting HIV and pregnancy prevention. A recent study led by Assistant Professor Lila Sheira, PhD, MPH, evaluated whether a peer-led, sports-based program in Zambia impacted girls’ and young women’s sexual and...

Policy Brief: Cost, Coverage, and Contraception – How Policy Can Improve Access for Community College Students

June 16, 2025

A new policy brief from Beyond the Pill and the Institute for Women’s Policy Research examines barriers to healthcare and contraceptive access for community college students and proposes policy recommendations to improve contraceptive affordability and availability.

HIVE helps people living with HIV achieve their family-building dreams

May 19, 2025

HIVE and their community will take part in this year’s SF AIDS Walk on July 20th. The event will be a celebration of their groundbreaking work, and an opportunity to make sure it continues.

Black Women Speak: An Abortion Storytelling Showcase

May 15, 2025

Join The UCSF Black Womxn's Health & Livelihood Initiative and Girlx Lab for Black Women Speak: An Abortion Storytelling Showcase. Listen to Black women share their stories as we journey to community healing and wellness. Food will be served and vendors will share information and products for...

What young people see as obstacles to UTI care

May 14, 2025

New research led by Jennifer Yarger, PhD, explores what young people perceive as barriers to care for UTIs.

Team Lily's innovative strategies to support pregnant people

April 30, 2025

The Foundation for Opioid Response Efforst (FORE), which awarded Team Lily one of their grants for programs developing innovative models to support people with substance use disorder, made a video highlighting the impact of their work.